Things rarely turn out the way we want them, and even less so for our protagonist, Ludvig Kahlen, played by Mads Mikkelsen, in the new film “The Promised Land.” The brazenly stoic war hero, now an impoverished farmer, comes home to cultivate the vacant, sterile and unkind heath, otherwise known as “the promised land.” Through heavy rains, harsh colds, blazing summers, love and loss, we follow the impenetrable resolve of Kahlen, against his more than formidable odds.

Exploring the plot of the film, at its bare bones, there’s a man, his sack of potatoes and the committee of landowners, who are aristocratic bigwigs — literally — that would rather see him dead than to have such peasantry wound the open fields of the heath.

Then, there is, of course, Ludvig’s “crew”: the best Kahlen could muster, a ragtag group of “outcasts.” They’re your average mix of runaways, wild men and women, fugitives and a priest, who I figured was a precaution to whatever trouble such a group might entail.

All of this is much to the aristocrats’ dismay, in particular Frederik De Schinkel, who insists on being addressed with the “De” before “Schinkel.” He stands firm in his entitlement to the heath and to pretty much anything under the sun that he hasn’t spoiled within his towering estate.

A line that stuck out to me in Schinkel’s introduction was, “God is chaos, life is chaos.” There is some kind of moral consideration in those words, and yet coming from the mouth of a middle-aged man with the emotional capacity of most tweens, they were grating on the ears. Much like a teenager who first opens Nietzsche and then assaults the dinner table with his empty citation.

That’s our primary antagonist Schinkel, a man cursed with so much wealth that his only preoccupations are drunkenness, rape and, of course, playing a game of tug-of-war with Kahlen’s heath. Those words fall flat on Kahlen’s emotionless, half-lidded stare. He doesn’t care, rather he’s performing, albeit with half effort, to the niceties of his new neighbors. And here we have our perfect standoff, the spoiled brat versus the wiser man.

Kahlen’s wisdom lies in his scarce speech, his careful words that quite often end whenever he enters any sort of social interaction. Kahlen is the type of man who can disarm, shoot and kill an ambushing assailant without a wrinkle of his brow, and yet, the advances of a woman read to him like string theory. He’s an awkward man. You get the sense that he had been alone far too long or had seen too much in his days of war. His life became less about the luxuries of humanity, and more about his duty to the king.

This aspect of Kahlen — his resolve — is utterly impressive to the point of concern, almost to a superhuman degree. Kahlen can wake up in the middle of the night and in one sniff of the air, he’s already clued in. There’s frost outside, a threat to the crops and, despite the freezing temperatures, every blanket in the house will be dedicated to said crops.

Despite the various setbacks to strike Kahlen’s goal, he rises again. He’s a man humiliated by the aristocrats, by his peers, by even the earth and its weather. The audience gets to see what it means to be a man of sacrifice, to move slow and steady even in the face of total annihilation. And it’s fascinating front to back, with effective action scenes, endearing romance and, surprisingly, the odd bout of dry hilarity.

“The Promised Land” sends audiences back into unscathed, 18th-century Jutland vistas and lantern-lit mansions with every pan of the camera. A sight to behold, a simple tale with complicated characters. A film that is equal parts brutal and subtle, and equally so worth your time.

5/5

jbatist2@ramapo.edu

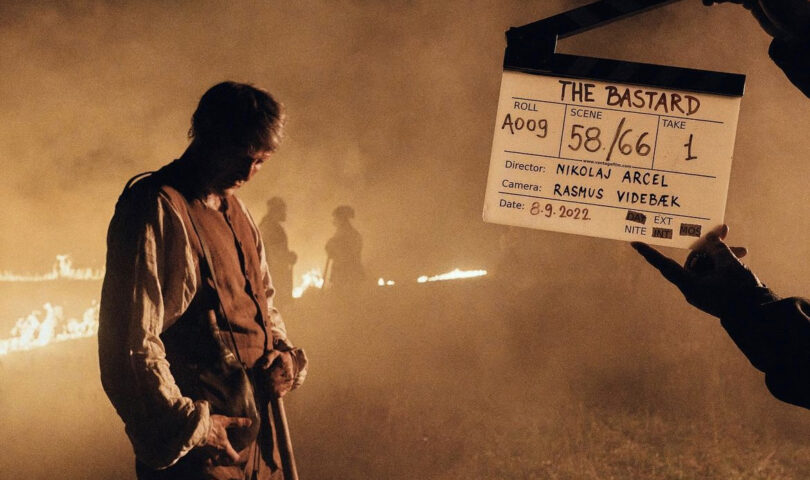

Featured photo courtesy of @magnoliapics, Instagram