The album cover and, as such, the music of Yeat’s new album “2093” is evocative of your typical Batman-esque protagonist. This image is completed with moral ambiguity and neon lights cutting through smokestacks, careening off draping leather coats.

Only Yeat isn’t so much the hero of this story. He’s somewhere in the middle, not a complete villain, but by no means a saint. Definitely not the chosen one destined to free us all from the oppressive neo-corporate hand. After all, the album kicks off with the song “Psycho CEO,” Yeat’s new-found identity within this dystopian future of “2093.”

In “2093,” we follow the Psycho CEO as he floats over beats that sound like they belong in a malfunctioning, barely flickering arcade game, rather than a contemporary rap album. The instrumentation brings to mind the electro-industrial techno of the early 2000s — something Mr. Anderson might dodge bullets in slow motion to.

The percussion ranges from fast-paced, speaker-blowing punches to more patient climbs and crashes, reminiscent of drum patterns on Kanye West’s “808s and Heartbreak.” Sometimes drums take a backseat, allowing room for vaporous synths to accompany Yeat’s autotune ballads of fast cars and faster money.

Where the album’s magic lies is in this juxtaposition of soothing, money-counting crooning, and the unexpected crash of drums, like a rush of cold water in your face after a night of warm rest. My favorite example of this rude-awakening transition starts in the song, “Bought The Earth.” Content-wise, the song hints at Yeat’s arrival to the top.

He’s at the top of the world — literally owning it — and yet he sings his victory over a morose drowning of rising and decaying violins: “Damn, what we could do? / Damn, I’m paranoid and rude.” He starts to look inwards and sees himself, he starts getting somewhere and then the beat switches abruptly.

Belting synths like Dracula’s entrance theme cast shadows on monotonous vocals and blistering bass lines. “A lot of things change, people don’t change / I just spent a quarter million on a fuckin’ chain,” he sings.

I imagine him, face illuminated by red brake lights of some future car, recounting all the empty decadence he’s been afforded. Buying the earth was just a plot to make his home in “2093” more complete, and it falls flat.

This is a prominent theme across the album, a surprising bit of cohesion considering Yeat’s previous works, which played more like a mishmash of disconnected studio sessions. Not to say I didn’t enjoy those as well, but, yes, the theme of materialism and the extreme highs and lows of being at the top are Yeats’ common curse. A curse he now shares with his standout feature, Drake.

Material wealth has had its way with Drake. In this setting, he’s Yeat’s Morpheus. He’s been here before and perhaps for too long. You can tell through Drake’s destitute recollections of the women and men he’s bested. He’s lapped his enemies so profoundly, he’s sitting in the stands watching them either drop out or shamble through gasping breaths.

You could translate this to the other of Yeat’s hip-hop forefathers who appear on the record, Future and Lil Wayne. I realized, listening to Future congratulate himself for slapping someone’s friend, that perhaps it’s not wisdom the three veterans are imparting.

Maybe what they’re offering is the mere fact that despite all these years, they’re still here. That towers of wealth can be lived in and thus, the veterans are the end result of what abundance creates or takes away. They are Yeat’s future asking if he should choose the red pill.

The record is quite the commitment, spanning 24 songs across an hour and 18 minutes. Most tracks tend to bleed into the next, without any significant sign a new song has begun. That’s a good thing, it means congruence, a lost art I’ve sparsely seen in this era of get-the-most-streams, sewn together rap albums.

It takes me back to the days of Kendrick Lamar’s “good kid, m.A.A.d city,” where hip-hop albums sought to house themselves more within their plots, instrumentation and themes. Yeat’s work here is nostalgia at its best, learning from our forefathers and still adding something new. So, hop in the time machine.

4/5 stars

jbatist2@ramapo.edu

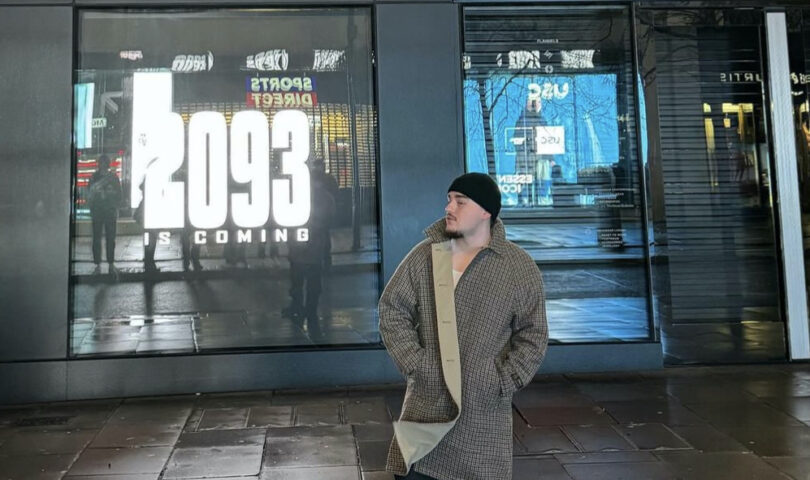

Featured photo courtesy of @yeat, Instagram